Here’s a lesson on trills in music, an ornamentation lesson presented on classical guitar. The focus here is on early music trills. I’ll be making many ornamentation lessons but I’ve started with trills since they are both very common and require more discussion than other common ornaments. Here’s the YouTube link if you want to watch it there.

Here are the Video Section Times

- 0:00 – Intro

- 1:23 – What is a Trill?

- 2:41 – How to Play a Basic Trill on Guitar

- 4:42 – How do Trills Affect the Music?

- 6:03 – Quick Tips for Students

- 9:19 – A Period Quotation

- 11:24 Length of Trills and Rubato

- 13:10 – Example of Trills (slurs, cross-string)

- 15:34 – Starting from the Written or Upper Auxiliary and How to Decide Which to Use.

What is a trill?

A trill is a musical ornament that consists of a rapid alternation between two adjacent notes, the written note and the upper auxiliary (note above). The two notes that alternate are usually a semitone or tone apart and are commonly diatonic (from the scale or key) but can also be chromatic. Trills start on the beat regardless of what note they begin with. Trills were also known as a shake from the 16th century until the early 20th century. Other names for trills were triller (german), trillo (Italian), trille (French), or trino (Spanish). Be careful with terminology, for example, trillo can mean something slightly different for early music vocalists.

What do trills do to the music? Trills can provide a number of musical results ranging from being decorative, melodically interesting, rhythmically interesting to adding dissonant tension in the harmony. They are sometimes notated in the score but also added at the performers discretion. Although they are ornamental and less important than the primary musical line, they can have a significant impact on the music.

Your first trills – If you’ve never played trills before, consider trying out my graded repertoire lessons books that introduce musical ideas slowly through repertoire. The first appearance of trills is in my grade 2 book. You may also want to practice slurs and rapid right hand exchanges from my technique book.

Other types of trills – This lesson is on the basic common trill in early music. Ascending and descending trills, trill-mordent, trill with terminations and various other ornament combinations will be covered in a separate lesson.

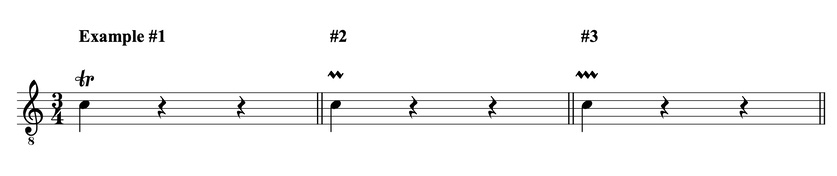

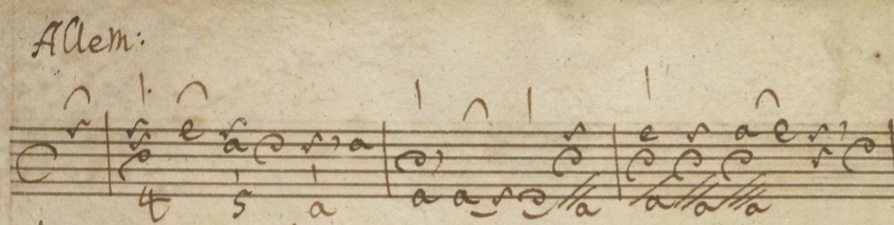

What do trills look like in music notation?

There are many different symbols to indicate trills, a few common ones are shown below. The first example is pretty clear. The second example of a short trill could still be performed as a long trill if the performer decided to do so. Keep in mind that early music scores and tablature have a wide variety of ways to indicate trills and ornaments and sometimes the symbols don’t call for a specific type of ornament.

Quick Tips Regarding Trills

- #1 Tip: Listen to lots of music with ornamentation from the time period and composer you are performing to be able to hear how trills should sound. Listen to performances on period instruments and the modern classical guitar. Absorb the style naturally through listening.

- Research the musical era, genre, style etc.

- Trills are decorative but can also have a function – Practice your music without the trill so you understand how the primary written notes should sound and function. When you add trills you need to keep the original function but also understand the impact of the trill and its affect on the music.

- Maintain the Rhythm – Never let trills disrupt the rhythm and beat of the original notes and beat structure unless they are part of a natural ritardando or rubato. Use a metronome to make sure.

- Don’t over-think it too much, put a metronome on to make sure you are rhythmically solid with the general beat and then try it with some rubato if desired or called for. It’s a rapid and flexible ornament within the structure of the beat. You can’t go too wrong if the written music is rhythmically and melodically intact.

- Trills are often added at the discretion of the performer. Some composers add some, all, very little, or no trills in the score but they are often added freely by the performer during the Renaissance and Baroque eras.

- A little bit of music theory can go a long way in deciding when and where trills are appropriate. For example, trills are often used to increased the tension of the V chord in a V-I cadence. You can check out some recommended Music Theory Books here.

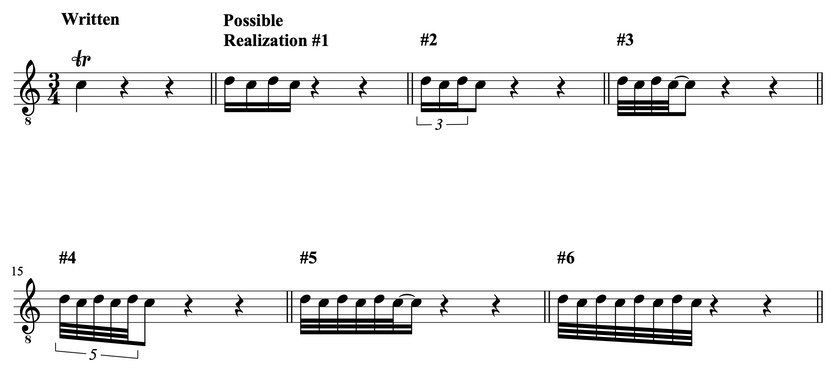

Examples of Short and Long Trills

Trills can be played with short or long repetitions depending on the context of the work, historical context, rhythm, and preference of the performer. Here are a few examples. Keep in mind that performers can use a micro amount of rubato within the delivery of trills. They might elongate the first note for example, which would change the way the rhythm is heard. I feel a bit silly writing out the realizations below as it’s more of a ‘by-feel’ or listening experience situation.

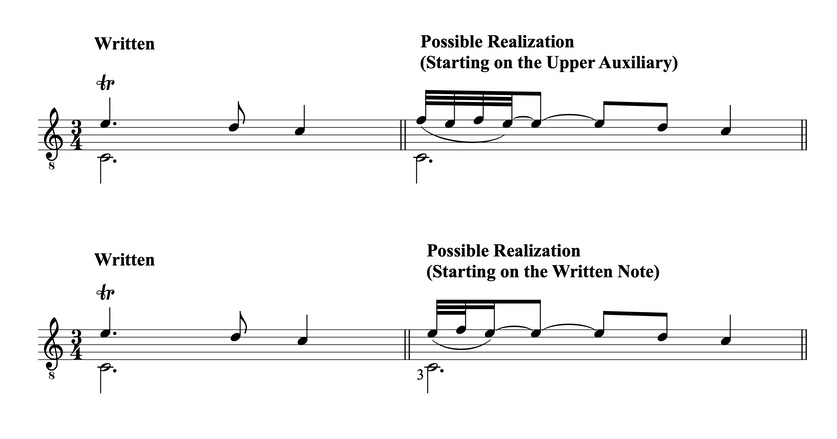

An Example of a Short Trill with Slurs in a Simple Texture

On guitar we often will use slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs) to play trills that are played on the single string.

An Example of a Cross-String Trill

Sometimes, either for necessity or preference, we play trills across two string rather than using slurs on a single string. Cross-string trills can sound very different than slurred notes on a single string. The result sounds less like a lute or violin and a bit more similar to a keyboard. It can be a more advanced technique and I also encourage you to mute the auxiliary note when complete so they don’t sustain at the same time (see video). Your personal preference and the musical era will decide if you use them. I almost always finger cross-string trills as a-m-i-p even though it involves an awkward cross. I mute with a.

Starting Note of Trills

Different Starting Notes? Depending on the musical context, time period, geographic location, and composer, trills will start on either the written note or the note above on the staff. There are some generalizations about this, such as the Baroque era preference for starting on the upper note and Romantic era from the written note. These generalizations are useful when starting out but they are only generalizations. Music is flexible and diverse so we want to understand the effect and function of each type of trill. However, especially in regards to the function of trills in cadential situations there are definite historical and functional preferences. If you are just starting out with trills in Baroque music you might want to stick with starting on the upper auxiliary for now to keep it simple and because it’s often the correct choice.

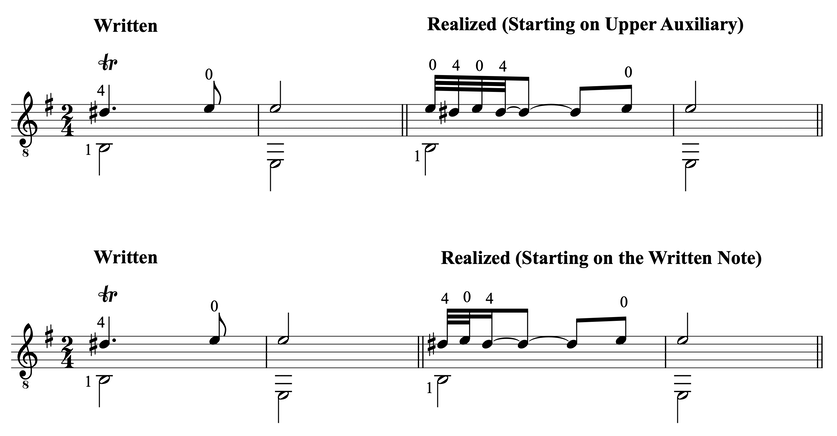

Starting on the Upper Auxiliary: This trill was especially common during the Baroque era and almost always preferred at cadential points during the Baroque. For example, in performances of Bach this is a very common trill and at cadences it will pretty much always be the preferred trill. The trill starts on the upper auxiliary (a note above the written pitch) and alternates with the written pitch. By starting on the note above the written pitch you are adding a non-chord tone on the accented beat which causes dissonance in the chord. The effect is increased tension with the harmony and then resolution when returning to the written pitch. Since the common dominant-tonic (V-I) cadence is already an expression of tension followed by resolution, the trill adds to the tension and intensity of the dominant chord before resolving to the tonic chord. You therefore compliment the composer’s intentions rather than distract from it. If you don’t quite understand the theory don’t worry, the ideas is simply: the sound of the upper auxiliary trill adds tension to a section of music before it resolves.

Starting on the Written Note: Starting on the written pitch and alternating with the upper auxiliary has a pleasant and decorative effect, a fluttering, which can be added quite easily to a passage without much interference to the harmony. Starting from the written pitch has less of a dissonant effect because the accented beat receives the written pitch which is a chord tone. Since this does not increase the tension or dissonance of the chord it is used less in cadential situations and more often for decorative effect. It’s a great trill to add mid-phrase so as to not distract from the forward movement and harmony.

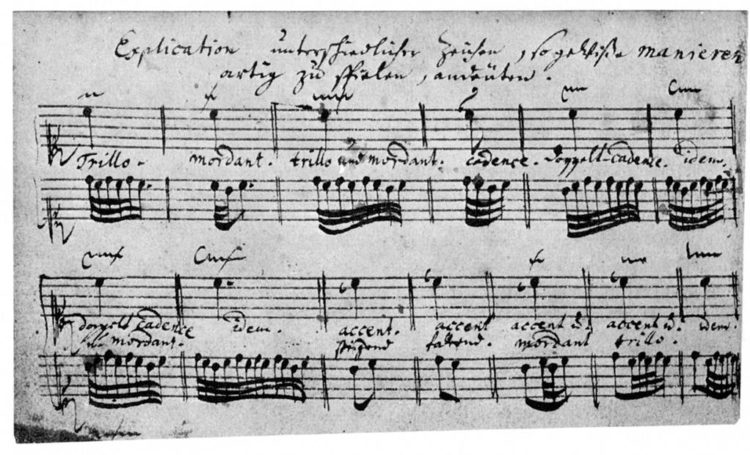

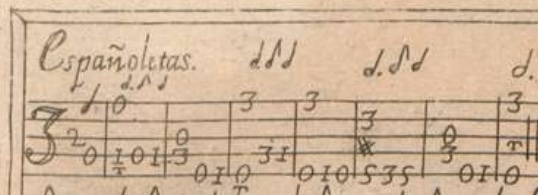

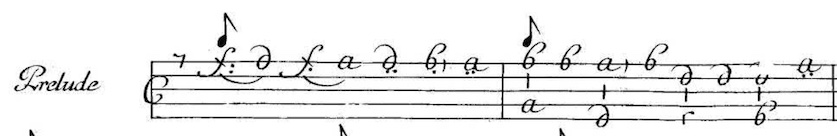

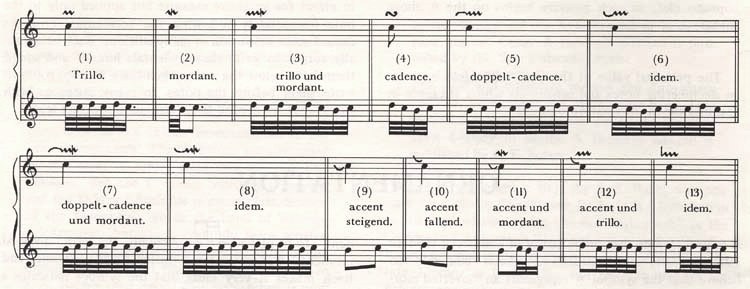

Historical context and source material. For example, Bach’s ornamentation chart gives us a good clue about how strongly he recommends playing trills starting on the upper auxiliary. But that is just Bach on the keyboard in Germany. Over in Spain on the Baroque guitar there is evidence that main-note trills were often employed by Gaspar Sanz, possibly preferred, especially when used decoratively in mid-phrase.

How to decide which note to start on

It’s all about context, historical awareness, and listening skills. You’ll want to research the composer, their music, the era, and the geographic location. But the easiest way to start building an awareness of performance practice is to listen to recordings or live performances by high quality professional musicians. After listening to the works of a composer by both historical specialists and modern performers you will start to hear what is acceptable and common in performances of the that music. If I perform a Renaissance lute work I’ll listen to performers who are specialists in Renaissance music. If it’s Dowland, I listen to Elizabethan lute music, vocal works, consorts and more. I’ll also listen to modern performers to hear how they have adapted the music to fit on modern instruments. If you can hear it naturally with listening skills you can imitate the sound in your own performances. You’ll be able to hear what sounds right. You can even start experimenting with imitating other instruments.

A further step is to do research on the era and composer. Bach, for example, created an ornamentation chart (see below) which gives us an idea of what he recommended. We shouldn’t look at his chart as a strict rule however, it’s more of a hint at what was common and preferred by Bach on the keyboard, especially when he notated it. It’s very possible that improvised trills in mid-phrase starting on the written note were completely acceptable. Again, it’s all about context and the musical result.

Baroque Tip for Beginners

Generalizations are fine when you’re just starting out. If you are playing trills in Baroque music, especially around cadences at the ends of phrases, start from the upper auxiliary. That is likely what is required and will serve you well for now. As you gain more knowledge and understanding you can start to question this generalization.

Mixing Trills and the Starting Note

Below is an example of mixed starting notes for trills.

- The original – You don’t have to play trills, the music is well written without them.

- From the written note – This sounds pretty good, especially if it was Renaissance music but I feel there is a lack of tension in the cadence.

- From the upper auxiliary – This sounds good too, especially if it was Baroque music but I feel the mid-phrase trill is a bit disruptive to the forward momentum of the phrase.

- Mixed – I like this one because the mid-phrase trill is minimal and calm while the cadential trill contributes to the tension of the V-I cadence.

Narrow the Scope of Inquiry

It’s important to research your music and narrow the scope of inquiry. Here’s an example of narrowing the scope:

- How did Baroque musician’s play trills?

- How did Baroque musicians in Germany play trills?

- How did keyboard players in Germany play trills?

- How did Johann Sebastian Bach play trills on the keyboard?

- How did Gaspar Sanz play trills on the Baroque guitar in Spain?

[FYI, there is evidence that main-note trills were often employed by Sanz, possibly preferred, especially when used decoratively in mid-phrase.] Try asking

Ask Yourself These Questions When Starting a new Piece

- Time Period

- Geography

- Composer

- Who were the composer’s influences?

- Instrument and Tuning

- Genre/style – Sacred music, secular music, vocal style vs instrumental style

- Form and style of selection, rhythmic feel, compositional style

- Type of notation or tablature used and related symbols

- Ornamentation style

- Are there any quotations of performance practice from the composer?

- Are there any articles or papers written on the composer/era/style?

- The list can go on forever

Situations

Suspensions Followed by Trills – When the upper auxiliary naturally creates a suspension from the previous note, starting from the upper note is likely elegant and preferable. A suspension creates tension by prolonging a consonant note (a chord tone) while the underlying harmony changes, often on a strong beat. By sustaining or restating the previous consonant note on the new harmony you create a tension-oriented non-chord tone. This combination of suspension and trill is an interesting marriage of two musical elements.

Mid-Phrase unobtrusive trill starting on the written note – If you keep the trill short and use a diatonic note (the upper auxiliary from the key) you can add this in without much disruption to any musical functions or intentions of the composer. It mainly becomes a decorative fluttering.

A Historical Quotation Related to Trills

It’s so interesting to look up quotations and advice from musicians that lived so long ago. Here’s one from Jean Baptist Besard (c.1567-1625) who was a lutenist and composer. The quote was found in Peter Croton’s book:

You should have some rules for the sweet relishes and shakes [trills] if they could be expressed here, as they are on the lute: but seeing as they cannot by speech or writing be expressed, thou wert best to imitate some cunning player, or get them by thine own practice, only heed, lest in making too many shakes thou hinder the perfection of the notes. In some, if you affect biting sounds…which may very well be used, yet use them not in your running [divisions], and use them not at all but when you judge them decent.

This is great because the advice is still so relevant. Imitate great players, down disrupt the written notes, and don’t over-use them.

Resources

The Guitar in History and Performance by Anthony LeRoy Glise – History and Performance Practice from 1400 to Today: A University Textbook for the Historical Study of the Classical Guitar. Nice Pictures, diagrams, etc.

The Complete Musician – An Integrated Approach to Theory, Analysis, and Listening. Steven G. Laitz is chair of the Music Theory and Analysis department at The Juilliard School and Professor of Music Theory at the Eastman School of Music. This is a comprehensive and proper theory knowledge text. For the serious student who wants to do things right. This is great book to own and will serve the serious musician very well. It might be unrealistic as a self-study book but it’s a must-have textbook for advanced theory and undergrad students. This is a theory book more than a performance practice book so not as much on ornamentation but all rest of it.

Guitar and Its Music from Renaissance to Classical Era (Oxford) by Tyler/Sparks – An excellent history and overview.

Performing Baroque Music on Classical Guitar by Peter Croton – This is more of a period resource book more than anything. But excellent from a period performance practice perspective.

A Tutor for the Renaissance Lute (Poulton) – Fantastic! Learn how to read Renaissance lute tablature and the techniques and performance practices that go along with it. This is actually for lute but intermediate students can tune down the 3rd string of the guitar to F# and go for it.

The Early Guitar: A History and Handbook by James Tyler – Great book as the above one as well but dives into early music.

Performance on Lute, Guitar, and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation (Cambridge) – A series of fascinating essays for the more advanced guitarist interested in performance practice. This is a tough read for beginners but a real eye opener otherwise.

And so many more. Leave a comment and suggest more below!

Thank you this is a very clear explanation of trills. I hope to use this information with your Sanz collection

This is a fantastic post, ornamentation is something, to me, that is a challenge and also a necessity to improve the artistic interpretation of a piece. I see this as useful for a lifetime practice. Thanks so much.